This paper was originally published in IEEE Transactions on Communications, vol COM-20, pp 511-15, June 1972. It was reprinted in Computer Networking edited by Robert P. Blanc and Ira. W. Cotton © 1976 IEEE.

MAX P. BEERE, MEMBER, IEEE, AND NEIL C. SULLIVAN, MEMBER, IEEE

Abstract—TYMNET is a large full duplex terminal oriented network that has been developed by Tymshare, Inc. The network is composed of over 100 interconnected computers serving as hosts or nodes. The evolution of this network was made possible by resolving a variety of hardware, software, and telecommunications problems. This paper describes the steps that took place in this evolution, the problems that were encountered at each of these steps, and how they were solved.

BACK in the early 1960’s, when time sharing was almost entirely an academic subject, it seemed logical to assume that interactive computing (time sharing) would be accomplished by accessing the computer by telephone. Since the cost of telephone calls increases according to their distance from the computer, it also became reasonable to place the computer in a location where each call to the computer would be a local or nontoll call. Thus was born the trend to expand a timesharing company by placing computers in each city where there seemed to be potential business. This trend started in the mid-1960’s.

This method of growth is both expensive and unwieldy. It is expensive because of the proliferation of computer centers built and maintained around the country, whether the center is built for current or predicted capacity. This method of growth is unwieldy because it deviates from the central intent of providing a standard grade of service to all customers wherever located. Each center has its own personality, created by the environment in which it is located and the caliber of people who run it, or are run by it. Since there are as many variables as there are locations and people, it is difficult to arrive at a service algorithm that will cause a predictably comparable grade of service to emanate from each of the related but unassociated service centers.

Growth is expensive because a projected total growth of one computer load spread across ten centers could, in the extreme, require the purchase of ten computers. By the time a computer becomes self-supporting, a new one must be moved in, killing profitability until the service loads build again.

Probably the biggest inhibiting factor to this method of growth (the proliferation of computer centers) is the most subliminal: the people involved. Each computer center has a unique operating staff and sometimes even supporting staff. Thus, across the many centers that make up a decentralized time-sharing company, it is easy visualize that in each personnel category there will be best person, whether operations manager, technical manager, operator, programmer, etc. But, these best people will not be together at the same location as a rule. We find then the hidden result of the mixture of good, fair and maybe even poor people, an equation approaching mediocrity.

Tymshare, Inc., was involved in this same situation until two years ago when projections of the then current trend, of a computer center in each major business area (San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York), began to indicate trouble. It became evident after closer analysis of the projected corporate model, that in order to maintain a viable business and to achieve profit goal Tymshare, must consolidate its computers into one location and transfer the computer power from that location to where it was needed.

The challenge was immediately evident: communication capability at reasonable cost. The need was equal evident that this communication capability had to dependable, error free, and interactive.

Tymshare chose to develop its own network from the communication common-carrier service. This network which Tymshare calls TYMNET, is presently in service using 80 Tymshare-built TYMSAT communication computers. Each TYMSAT uses a Varian Data 620 computer.

Each step in the development of this network resulted from the solution of specific problems, often bringing new problems to light in the process of solving old ones.

The genesis of Tymshare’s XDS 9401 system was ARPA project SD-185 at the University of California, Berkeley. The software system they created was a full duplex system. The characteristics of a full duplex system were so favorable that Tymshare decided to employ it in any type of Tymshare-built network.

Full duplex operation is characterized by all printing on the terminal being transmitted from the computer. If a user strikes the letter Z on his keyboard, it is transmitted to the computer; the computer then transmits the character back, and the Z prints on the user’s terminal. The user then knows that the character has been receiver correctly by the computer. The greatest advantage of full duplex operation occurs when the terminal is printing or when a program that does not yet require input is in operation. In this case, the XDS 940 defers the echo until the proper time. This allows the user to enter characters ahead of the operations that require them. The advantages of a full duplex system are not obvious when described, but once ingrained in the habits of the user, they become very difficult to forgo.

The first attempt to spread computer power using an “extension cord” method was via frequency-division multiplexing. This was a simple extension of the teletypewriter channel to the computer.

The results were disastrous. Difficulties included bad equipment, noisy lines, and irate customers.

Although this service marginally filled Tymshare’s need, serendipitously as it worked out, it was at that time deemed illegal by the Bell System. Tymshare was forced to seek a replacement method. The method, as it evolved, was to utilize a minicomputer and a form of time-division multiplexing using logical records as a replacement. This method of operation has since become the keystone of the network.

The first attempt to build this device, called a TYMSAT, solved the legal problems, but it did not solve the technical problems. In fact, it introduced some new ones.

The line problems previously experienced had not been solved and a new problem, the “sticky keyboard” problem, became very bad as distances increased.

The sticky keyboard is a problem associated with full duplex systems.

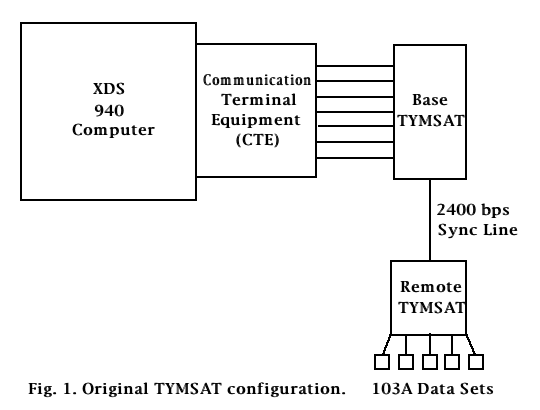

When a remote user typed a character, the character passed through a TYMSAT, the line, another TYMSAT, and into the XDS 940 where it was echoed by the XDS 940, passed back through the telephone lines and the two TYMSAT, and printed on the page (see Fig. 1).

This caused a noticeable time lapse between the depression of a key by the user and the character printing on the page.

This is the sticky keyboard phenomenon.

The experienced user learned to ignore this delay. The occasional user never felt comfortable with this situation. The temptation to convert to half-duplex was great, but Tymshare persevered. The cost of this extension cord was high, since it required two minicomputers, TYMSAT, to serve every location to which service was provided, and the terminal speed was limited to 10 characters/s.

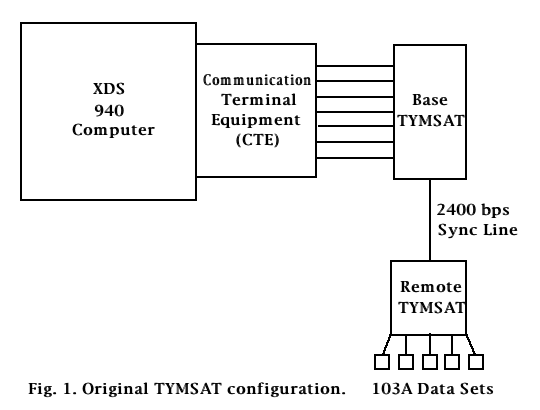

The next stage of development is shown in Fig. 2.

In this stage, the major step was the replacement of the XDS 940 Communications Terminal Equipment by a direct memory interface.

With this method, the speed restriction of 10 characters on a single channel was removed.

Transmission speeds could be raised to 15 and 30 characters/s.

Software sampling was used to allow 10-, 15-, or 30-character/s terminals, operating in several codes to be used.

Since the sampling was accomplished by software, separating the lines by speed or code was not required.

An IBM 2741, a 10-, 15-, or 30-character/s terminal, an ASCII code terminal, or a variety of other terminals could use the same telephone number by the simple expedient of typing an identifying character as the first character in the session.

This character identifies the terminal, code, and speed of transmission.

Since the entire system uses only ASCII internally, any conversion of non-ASCII code is done at the remote TYMSAT.

The monitor in the XDS 940, however, may indicate that the characters received or transmitted on a specific channel are to be unconverted.

This is used for input and output to plotters, card readers, and numerically controlled devices.

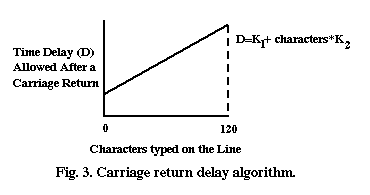

The driver for each terminal keeps track of the position of the printing head for terminals with slow carriage return time.

With the reception of a carriage return character from the computer, only enough time is allowed to elapse for the carriage to return from the print position.

This method maximizes the output of the terminal.

The carriage return delay D is approximated by a linear function, whose constants K1 and K2 are dependent upon the terminal (see Fig. 3).

The sticky keyboard problem was removed by having the echoing done by the remote TYMSAT. If the remote TYMSAT were to do all the echoing, the advantages of full duplex would be lost.

The remote TYMSAT would do the echoing if: 1) no characters were waiting to be printed; 2) no characters were known to be coming down the channel to the remote TYMSAT from the XDS 940; and 3) the XDS 940 had not signaled the remote TYMSAT not to echo.

If the remote TYMSAT did not do the echoing for one of these reasons, control information would be sent down the channel to signal the XDS 940 that these characters were not echoed. The XDS 940 would then echo the characters at the time the program requested them. This would place the character at the proper place within the character stream to retain the advantages of full duplex.

With the elimination of the sticky keyboard problem, two major areas of concern remained. The remote TYMSAT were still at the mercy of noise on the synchronous telephone lines and the power of a single XDS 940 could be distributed only to two locations.

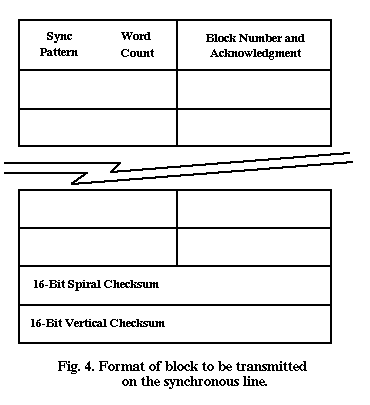

The common expedient of checksumming is used in an uncommon way to detect the errors that occur on the synchronous lines that connect the remote TYMSAT to the base TYMSAT [1]. The stream of outgoing characters on the synchronous line is divided into blocks of between 12 and 66 characters. A 16-bit vertical checksum and a 16-bit spiral checksum are placed at the end of each block (see Fig. 4).

Since the connecting network is operated in synchronous and full duplex mode, a continuous conversation is maintained between the TYMSAT. When a block is received, the number of that block is returned to the sending TYMSAT as part of the next outgoing block. If a block is not acknowledged, it is automatically retransmitted by the sending TYMSAT. If an error is detected, the block is disregarded and not acknowledged. The major cause of a checksum error is noise on the line; a record of the number of errors per minute that occur between TYMSAT will indicate the condition of the line. Each TYMSAT is now set to indicate on a monitor terminal if more than ten block errors occur per minute. If these errors persist for a period of several hours or if the line goes out completely, the common carrier is notified.

The Bell System tariff allows for one error in 100 000 good bits. Tymshare’s system will compensate for error rates grossly below those standards. This algorithm allows for an undetected error rate better than one bit in 4 × 1013 bits transmitted.

Note also that a burst of errors may still only show up as one error because of the block mode of error detection, whereas white noise would result in many blocks of data being in error and many retransmissions.

Because of this, switching noise is not a great problem.

The link between the user terminal and the computer is the least protected line. This is partially covered since the remote echo and full duplex method of operation allows the customer to visually verify that each character sent was actually received by the TYMSAT.

A rate of transmission of at least one block every ½ s and at most one block every ¼ s will support about 57 simultaneous active users on a 2400-bit/s line. This is possible because the average user typing on a circuit has an average activity of from 2-4 characters/s. Under normal operation, about 240 characters/s can be transmitted on a 2400-bit/s line.

One of the characteristics of interactive time sharing is that the out-bound stream of characters is about ten times the in-bound volume and the central computer has complete control over the out-bound stream. Since it has adequate buffering capacity and the logic to juggle bits in order to keep them flowing to the capacity of the line, a good degree of line efficiency is achieved. In Tymshare’s most efficient format outbound from the computer, 16 characters of overhead and 58 characters of data are transferred each ¼ s. As a result, the maximum efficiency is (58 × 4) /300 = 0.77 = 77 percent.

Fig. 5 Presently 19 XDS 940 and 3 PDP-10 computers are serviced by 80 TYMSAT.

Flexibility was the last remaining problem in Tymshare’s arrangement of remote TYMSAT and base TYMSAT. The configuration shown in Fig. 2 restricted each base TYMSAT to two remote TYMSAT. The reason for this restriction was the performance of the Varian Data 620. It could handle only one 2400-bit/s line using the software sampling technique.

A Tymshare-designed interface assembled the bits received from the synchronous line (operating at 2400, 4800, or 7200 bit/s; with a faster central processing unit, 9600 bits/s is also permissible) and assembled them into a 16-bit register, thereby dividing the number of interrupts by 16. In addition, the interface has a zero detect state which, when invoked, ignores the marking state until a zero bit has been detected. This allows the time between records to be free of interrupts.

This reduction of interrupts allows up to three synchronous lines (eight with a faster central processing unit) to be handled by a single remote TYMSAT. Fig. 5 shows a general diagram of part of the “daisy-chained” network.

Although the network shown in Fig. 5 is capable of a wide distribution of computer access, it had the unfortunate characteristic of being very rigid in its structure. If a user called port 31 (port is Tymshare’s name for the 103 data entry point on the remote TYMSAT) of remote TYMSAT 40, he would be accessing a specific computer such as number 12. If the user wished to use computer number 11 instead of computer number 12, he would have to dial a telephone number associated with computer number 11. The path the characters took was dependent upon tables assembled into the code at each TYMSAT [2]. These tables establish the full duplex channels within the network. When a path change was required (which often happened), all TYMSATs through which the path traveled had to have simultaneous software changes.

This process of software changing required a great deal of coordination and effort. To avoid this problem the network supervisor concept was evolved.

If the tables within the TYMSAT could be altered by program control, a system could be established to allow the user entering the network at any point to access any computer. This concept was implemented in the following manner.

One XDS 940 is assigned the additional task of remembering the state of all channels in all TYMSAT’s. When a user calls a port on the network and identifies his terminal type, speed, and code, a special full duplex path is established through the table structure in each TYMSAT to the network, supervisor computer. The network supervisor then asks for the user name and the password. After these have been correctly typed, the network supervisor looks into a file to determine the computer on which this user has stored files. If the user has files on several computers, he may indicate that he wishes a computer other than his primary one by typing the number of the host computer which he wishes to use. For example,

PLEASE LOG IN: JONES: 12;;

indicates that the user jones wants logical computer number 12. At this time the network supervisor examines its table of paths between the TYMSAT the user has entered and the host computer he wishes to use.

Using these tables, a route is chosen between the TYMSAT and the host computer. This route is based on the load, the least number of intervening TYMSAT’s, and the error rates on the lines. This ability of the network supervisor equalizes the load on the network whenever possible.

The network supervisor then sends control information to each TYMSAT along this route, changing the necessary entries in the switching tables within the TYMSAT to provide a virtual channel between the terminal and the goal computer.

It would appear that a software crash of the network supervisor would wipe out this network and prevent access to all the computers. To prevent this occurrence, the network supervisor resides in several computers at once [2]. The others are dormant, activating only about once each minute to receive a confirmation from the network supervisor that it is still active. If this confirmation is not received, the next network supervisor takes over by probing the network to find its structure.

If a line between nodes fails, this information is communicated to the supervisor on the supervisory channel and the supervisor restructures the table to use alternate synchronous lines, if available.

The ever increasing number of time-sharing terminals, each with its own unique features combined with a growing variety of computers and each with a scope of jobs it can do most economically, makes a single connecting network very advantageous. Fate and design have serendipitously resulted in TYMSAT being a network flexible enough to easily adapt to new terminals and new computers, an ever changing, ever evolving environment.

[1] A. K. Worley, “Practical aspects of communications,” Datamation, Oct. 1969.

[2] L. Tymes, “Tymnet-A terminal oriented communications network,” Spring Joint Computer Conf., AFIPS Conf. Proc., vol. 38, pp 211-16. Montvale, N. J.: AFIPS Press, May 1971.

Manuscript received May 10, 1971. This paper was presented at the 2nd Symposium on Problems in the Optimization of Data Communications Systems, Palo Alto, Galif., October 20-22, 1971. The authors are with Tymshare, Inc., Cupertino, Calif. 94014.